Canine Elbow Dysplasia Diagnosis and Treatment

Dysplasia simply means abnormal development, and unlike the term hip dysplasia, which describes a specific condition, elbow dysplasia is a broad term encompassing several conditions affecting the elbow. Elbow dysplasia can occur when the three bones comprising the elbow (the humerus, radius, and ulna) don’t fit together properly or when the dog suffers from primary cartilage disease.

Whatever the cause, all forms of elbow dysplasia can lead to progressive osteoarthritis, degenerative joint disease, and erosion of the cartilage within the joint—all very painful conditions that will eventually limit a dog’s mobility and severely impact quality of life. With early detection and intervention, we can typically create better outcomes and slow the progression of degenerative joint disease, and replacement techniques offer help for dogs with chronic debilitating arthritis.

Diagnosis

Most dogs will exhibit signs of elbow dysplasia between 6 and 9 months of age. However, first-time lameness stemming from elbow dysplasia can appear at any age. Lameness may occur in one or both front legs, and many dogs will stand with their front paws turned outward.

Properly diagnosing the cause of elbow dysplasia requires a combination of a physical exam, a thorough history, x-rays, computed tomography, and arthroscopy. Arthroscopy is a minimally invasive procedure during which we insert a small camera into the affected joint through an incision just a few millimeters long. Arthroscopy has become the gold standard for diagnosing and treating elbow dysplasia because it gives us direct visualization of the elbow so we can make a definitive diagnosis and possibly treat the cause of the dysplasia in one procedure.

Diagnosed causes of elbow dysplasia could include the following:

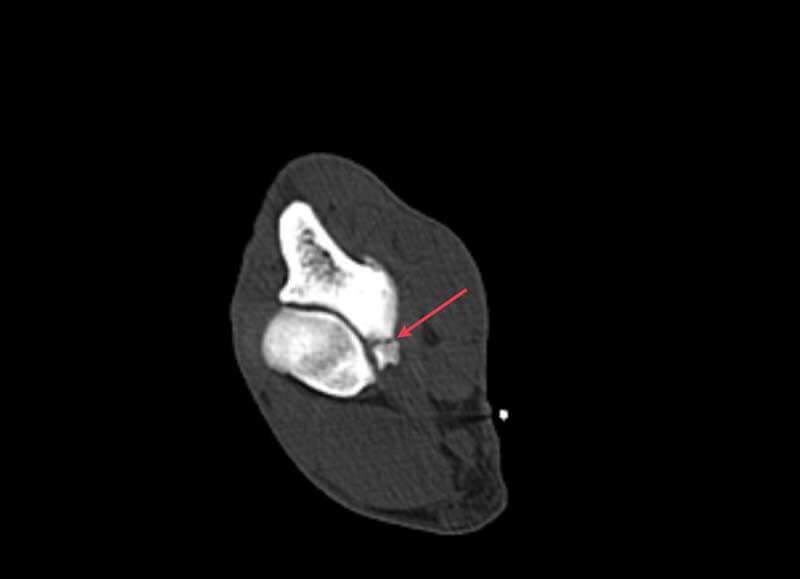

Fragmented Coronoid Process (FCP)—FCP is the most common cause of elbow dysplasia and usually stems from abnormal wear or stress on the coronoid process, which is a small prominence of bone on the inside ulna. This abnormal wear and tear causes a microfracture, and the loose fragment can cause irritation, inflammation, and osteoarthritis. Removing the fragment may improve clinical signs, but the underlying cause of the abnormal wear of the cartilage may still need to be addressed.

Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD)—Often called a cartilage flap, OCD is an abnormality in endochondral ossification that results in a poor connection between the cartilage and the bone. The weak connection causes the cartilage to separate and peel away from the bone, leading to lameness, pain, and progressive osteoarthritis.

Ununited Anconeal Process (UAP)—A condition seen most often in German Shepherds, UAP is a lack of fusion of the anconeal process (a prominence of bone on the ulna and behind the humerus) by 20 weeks of age. Though UAP is present from an early age, it can also be the cause of acute onset lameness in older animals. Surgical stabilization of the UAP is possible in young patients, and excision is needed for older patients.

Elbow Incongruency—In a normal elbow joint, the humerus, radius, and ulna fit together precisely to form a congruent joint. A length discrepancy or conformational change in any one of the bones can lead to incongruence of the elbow, resulting in pain and progressive osteoarthritis. Both lengthening and shortening techniques exist to reestablish congruence, but early detection is essential for successful treatment.

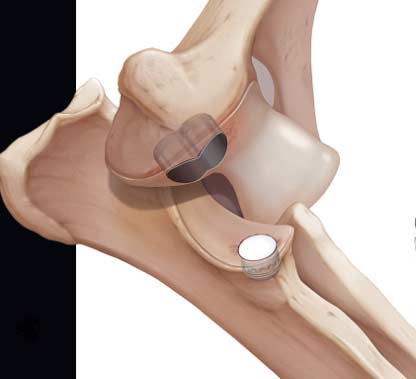

Medial Compartment Disease (MCD)—When progressive osteoarthritis from elbow dysplasia results in a complete erosion of the cartilage on the weight-bearing surfaces of the medial joint, we call it Medial Compartment Disease (MCD). In this end-stage elbow dysplasia, the medial joint collapses, and bone (humerus) grinds against bone (ulna). MCD can be diagnosed in dogs as young as 6 months old or may become apparent at any age. Limping, changes in activity levels, swollen or painful elbows, decreased performance, and behavioral changes are all clinical signs, but many of these symptoms don’t become apparent until later in the dog’s life when the osteoarthritis is severe. Replacement/resurfacing techniques can return once severely arthritic patients to their normal, pain-free activity levels.

Treatments

Once we have a definitive diagnosis, we can recommend an effective treatment based upon the specific condition and the stage of the disease process.

Elbow Arthroscopy—Surgical intervention early on with arthroscopy enables us to evaluate the medial compartment of the joint, remove loose fragments, and smooth the joint surface (chondroplasty). In dogs less than a year old without signs of cartilage wear or full thickness erosion, arthroscopy may provide more comfortable mobility, but it will not eliminate the osteoarthritis and the potential for progressive MCD. As MCD progresses, lameness, pain, and limited mobility result.

Canine Unicompartmental Elbow (CUE) Resurfacing—Oral medications, joint injections, and physical therapy may be helpful in some cases for a period of time and should be discussed with your family veterinarian. When surgical intervention is deemed necessary, which is often the case, Canine Unicompartmental Elbow (CUE) resurfacing is a safe and effective option when arthroscopic treatment and nonsurgical options are no longer helping. During the procedure, we use a CUE implant to relieve the bone-on-bone grinding in the medial compartment while preserving the dog’s good cartilage in the lateral compartment, resulting in reduced (or eliminated) pain and lameness.

If you are a referring veterinarian and would like to learn more about our elbow dysplasia diagnostic and treatment options, please call (406) 218‑2800.